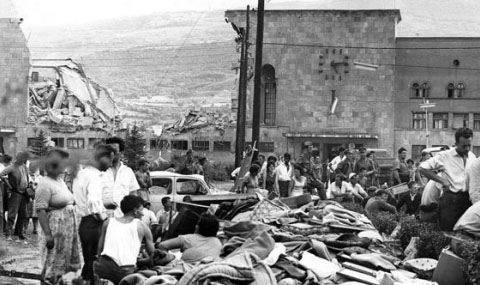

The trains were lying on the railways waiting for the dawn, the platforms where still empty, soon to be filled with the passengers and the agitation of early morning. But this wasn’t to be an ordinary day for the station. The land roared and shook and the dawn lingered forever on the station clock. The trains were never to depart, the passengers to travel. The left wing of the station and its central dome fell apart under the earth’s rage, leaving the building devastated. This landscape of ruins was ubiquitous in the city on that day. The disaster was bewildering. In the archive pictures, distressed citizens are seen finding their way through the rubbles and looking astray for disappeared family members and friends. Disfigured buildings stood fragile. The sky weighed heavy over the ravaged cityscape, filled with dust and thick with the souls of the departed citizens. Skopje’s weeping was heard worldwide.

5:17 am, 26 of july 1963, is a date that marked the city of Skopje and its future development. The sight of the amputated station, and the ravaged city are premonitory. A page in the city’s history is turned, and a new chapter is announced. It is a farewell to the city of Uskub, as was Skopje known under the Ottoman rule; when the station was first built in 1873. It was the first railway station to link Skopje to Thessaloniki, thus bringing the Aegean sea within the reach of western Europe.

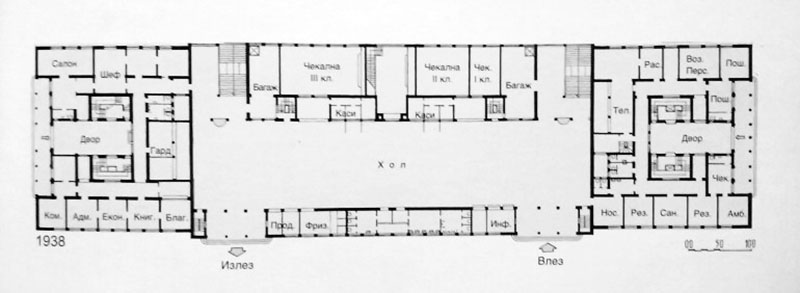

In 1918, Yugoslavia is established ending the ottoman rule in western Europe. In 1937, the train station is demolished and a new building was designed by Serbian architect Velimir Gavrilović. The station, in neo-byzantine style, with travertine stone facades boasting the clock’s dials and hands over the central entrance, stood proudly on the same site. It was one of the biggest in the Balkans. The building comprised a central part, the main hall with an impressive gallery on the upper floor, and a central dome. The two wings on each side had separate entrances. The interior walls and floors of this transport temple at the beginning of the 2oth century were paved in marble and adorned with frescoes by the Macedonian artist Borko Lazeski.

In the actual city museum, there isn’t any archive to consult on the train station; neither as a building nor on its architect, nor on Borko Lazeski’s work. I had to pull up the pieces of the station story from a variety of sources to reconstitute its narrative.

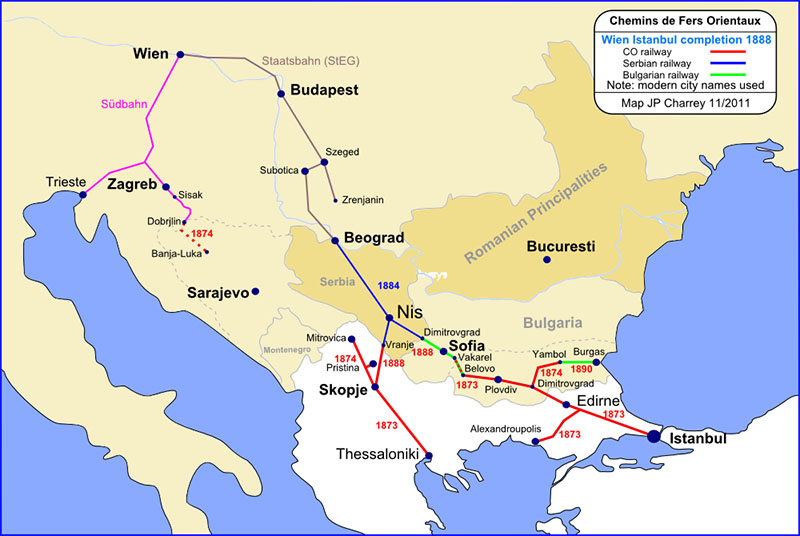

A long and complex story lies behind the construction of the railway networks at the end of the 19th century. A geopolitical weapon and a strategic feature of territorial control, the outline of the railway networks materialized the aspirations of the powers in control. This is a turbulent epoch in the Balkans under a weakened Ottoman empire after the rising of nationalist tendencies (Serbian revolution 1804-1815, Greek war of independence 1821-1832, Bosnian uprising 1831-32) and the Crimean war 1853-1856. The Ottoman empire occupies the whole Balkan territory at the exception of Serbia and Montenegro, and around 1860, not a single railway line is laid out in the territory. The reluctance of the Ottomans to establish railway lines, apart from economic difficulties, is the fear of a connection with Europe, its political adversary. At the same time, the militaries knew of the importance of the railways to quickly control rebellions on the territory. In 1867, Sultan Abdul Aziz, after a visit to the Exposition Universelle of 1867 in Paris, and probably inspired, gives the instructions to construct a railway line connecting Istanbul to Europe. It is Baron Hirsch, the founder of the Société Générale pour l’Exploitation des Chemins de Fer de la Turquie D’Europe that obtained the concession for the construction of the railway from the ottoman government. One of its lines links Uskub (Skopje) and Thessaloniki. But in 1871, the project comes to a halt, the predecessor of Sutlan Abdel Aziz, Mahmoud Pacha, opposes the connection with Europe and privileges the one with Rumania and Russia. A new convention is signed with Baron Hirsh’s society in 1872: to complete the line in construction and achieve new connections. Among the new connections is the one linking Skopje with Mitrovica (actually the north of Kosovo). Between 1872-74 the line connecting Thessaloniki, Uskub and Mitrovica (362,890km) is achieved.

The Chemins de Fer Orientaux is the first company to exploit the Thessaloniki-Skopje line. But the project was once again stopped: the Ottoman Empire is bankrupted in 1876 and facing war with Russia and other Balkan territories. The belligerences ended with the San Stefano agreement in 1878 and a new territorial division achieved in the Berlin Conference of the same year. The railway lines are an issue in this conference, since segments of it were scattered on the Balkan territory achieving no connection between the restructured geography of power. It is the convention of the 9th of May 1883 that will outline the railway connections between the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empire, Serbia and Bulgaria. In the articles 3 and 4 of the convention, a junction is to relate the two railway segments Niš-Vranje and Thessaloniki-Mitrovica. Skopje became the point of junction. On the 19th of may 1888, the official opening of this line announced the connection of Europe to the Aegean sea. The segment relating Skopje to Vranje, on the Serbian frontier is 85,109km long and crosses the Preševo valley which separates the Morava and Vardar bassins. The Italian company Vitali had the concession to construct it and the works started in 1885. This line still operates today. It takes 2h30 to reach Vranje from Skopje, with 2 stops in Kumanovo and Tabanovce. The crossing of the Preševo valley must be amazing, as the history that lies behind the valley.

The Oriental Express, inaugurated in 1883 will gradually integrate segments of these lines in its railway exploitation network. Skopje will soon become part of some of the routes of the famous train: of the Simplon-Orient-Express from 1919 to 1962 and of the Arlberg-Orient-Express from 1932 to 1962, one of the routes connecting: Budapest, Kelebia, Szabadka (Subotica), Belgrade, Niš, Skopje, Devdelija (Guevgueliya), Idomeni, Thessaloniki, Amfiklia, Athens, Piraeus. And then from 1962-77 of the Direct-Orient-Express connecting the United Kingdom, France, Switzerland, Italy, Sloveny, Croacia, Serbia, Macedonia, Greece, Bulgary and Turkey. Isn’t a dream story for the station, a golden age?

As the city of Skopje itself, the station passed from hand to hand during the 20thcentury. Its railway lines were successively under the exploitation of the Serbian State Railways in 1913, the Yugoslavian State Railways in 1929, the Bulgarian State Railways in 1941, the Macedonian State Railways in 1944/1945, the Macedonian Federal Railways in 1945, the Yugoslav Railways in 1945, the Directorate of State Railways in Skopje in 1945, the Rail transport company-Skopje in 1963 until it was destroyed by the earthquake.

But the past splendour is long gone and the station’s destiny was to be the immortal witness of a tragic event, a reminiscence of an epoch. It is converted into the City Museum of Skopje. Located on the boulevard Kiril i Metodij, you approach the old railway station on a wide sidewalk. A strip of grass marks the beginning of the station area and is scattered with steles and sarcophaguses from Scupi, the archeological roman settlement. The big park that laid in front of the station has disappeared, probably no longer needed as a buffer zone for the hustle and bustle that usually surrounds railway stations. It is replaced by a far lesser charming neo-classical building from the 2014 Skopje project. The damages caused by earthquake are intentionally left visible on the building’s façades, while the interior has been rearranged for exhibitions and artistic venues by Croatian architect Gjuka Kavurić.

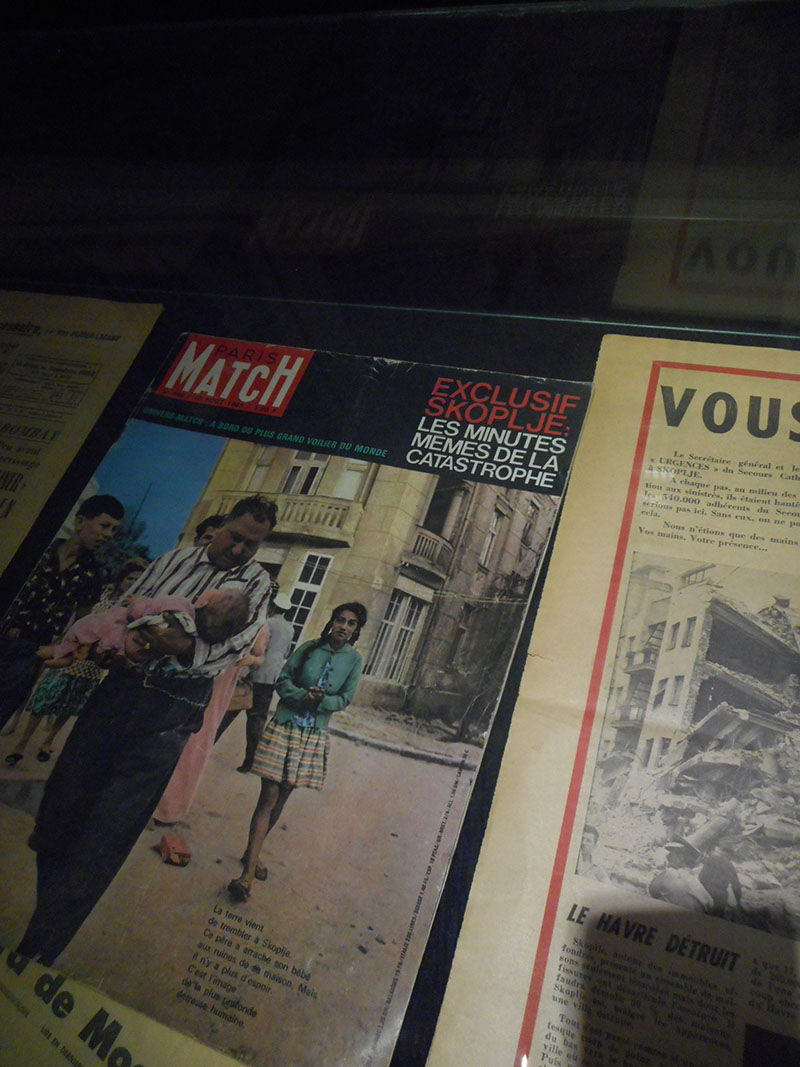

“Walk through the past” is a permanent exhibition of the museum. It narrates the history of the city of Skopje from the prehistory to the beginning of the 20th century. A special feature of the exhibit is the one that narrates the episode of the earthquake. It features big panels of black and white photographs, international press releases where Skopje made the front page, vestiges of abandoned children toys, an interior of a damaged house, aid boxes from different countries. Near the entrance to the museum, you can read the words Tito said in the disaster’s aftermath, engraved on a commemorative plaque. They were later reproduced on one of the remaining exterior walls of the west wing. But for a visitor looking for some memories still lingering in the space, it is a disappointment. The space has been stripped of its “time” patina and no hints to its past usage are found: not a timetable of the ghost trains, not a trace of the thousand steps that crossed la salle des pas perdus of the station’s main hall, no sign of the heroic frescos… all has vanished, and one is left surrounded by the white and grey walls of the exhibit space.

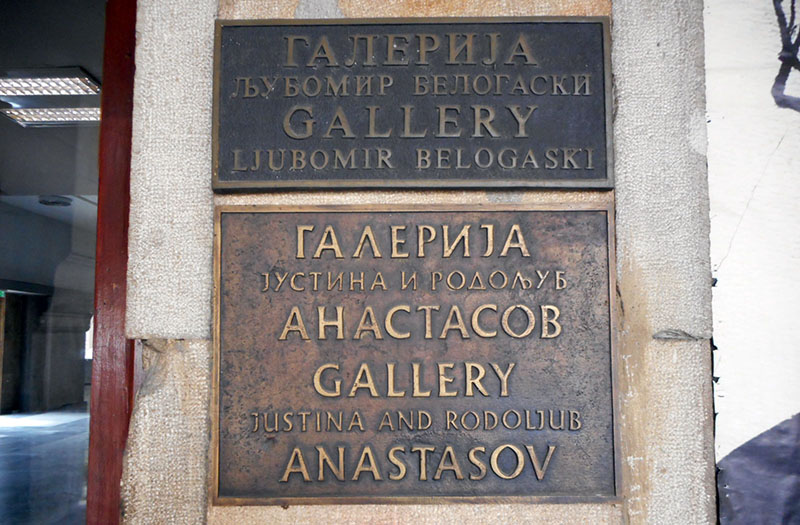

The museum dedicated two of its exhibit galleries to Ljubomir Belogaski and to Justina and Rodoljub Anastasov. But unfortunately not a permanent exhibit or expository material is seen of the many works donated by both artists to the city museum already functioning in 1974. Wondering inside the building, I saw an open door leading to a staircase to the upper floor. To my big surprise, the walls are covered with beautifully framed posters of the artist Rodoljub Anastasov. I thought it was a pity to have them isolated as they already give an insight of the artist whose name appears poorly on a signage with no further information.

Unfortunately, the adaptation of the station leaves little chance for storytelling, for tracing the station’s past life along the orient express lines. For the visitor, the remaining platforms are not accessible. I went up the terrace of a nearby mall to have a look on the station’s rear side. The fringe of leftover platforms was clinging desperately to the station to avoid drifting on a land ravaged by the excavators, trucks and cranes of the project developing on the extended plot behind the station. The station will soon be immersed in the weave of this new building complex, Diamond Skopje. In the project perspectives, a garden is designed in front of the remaining right wing of the station, the steles and sarcophagus bordering the sidewalk have disappeared and an elongated building stands where the old platforms once stood, lurking behind the station. Again, no space, literally, is left for memory which is now embedded in leisure consumption. But there is a story to tell, if property developers, investors and cultural organisations decide to give this place a voice.

In the earthquake’s aftermath, a new railway station was built; it was an architectural stunt achieving at the scale of the city almost the same effect as the old railway station in its times. Built by Kenzo Tange, the new railway station is one of the architectural pieces of his reconstruction plan for the city designed in 1965. Here is a glimpse at this new station, as a souvenir of my walk on a sunny day from the old railway station until the new, mythical one…

Links and article that have been the support for this article:

- Sultan Abdul Hamid Photo Collection, Istanbul University Library.https://marh.mk/стара-железничка-станица-скопје-вели/.

- Snappy goat.com.

- The Macedonian railways webpage: http://mz-rail.atwebpages.com/history/history_en.html.

- Henry Jacolin, “L’établissement de la première voie ferrée entre l’Europe et la Turquie. Chemins de fer et diplomatie dans les Balkans”, Revue d’histoire des chemins de fer [En ligne], 35| 2006, mis en ligne le 25 août 2011, consulté le 09 avril 2019. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rhcf/414; DOI: 10.4000/rhcf.414