BIOGRAPHY OF AN ARCHITECTURAL WORK:

TELECOMMUNICATIONS CENTER-SKOPJE

ARCHITECT JANKO KONSTANTINOV

Jovan Ivanovski, Ana Ivanovska Deskva, Vladimir Deskov, Skopje 2017

I have been living in Skopje for over 2 years now and my frustration keeps on regarding my knowledge of the built environment. So many things to tell, and so little I know; it brings a sigh each time one of these buildings that stand proudly in the cityscape catches my eye. Some are old and decrepit like the Goce Delchev student dormitory by architect Georgi Konstantinovski (1969); others keep very young because they are still implicated in the life of the citizens like GTC Shopping mall by Živko Popovski (1973), or became a landmark, a live symbol of the aspirations of the city at a certain time like the Telecommunications center by Janko Konstantinov (1974-1981). North Macedonia has been a contested territory, and its built patrimony reflects it. For an architect, the golden age of the city is probably divided in two periods. The first from the 40s till the 70s announces the adoption of modernist architecture when the Republic of Macedonia, a young country of the Yugoslav federation, was developing and searching for its architectural language. Hence, Blue Crow Media published a beautiful map on Skopje’s modernist architecture. The second from the 70s till the 90s, when the 1963 earthquake triggered a wide reconstruction of the city; which achieved like the authors say a “widespread acceptance and affinity towards sculptural forms in reinforced concrete built in Skopje in the late 1960s and early 1970s”.

The cityscape of Skopje is marked by the 70s architecture. In this mostly modern cityscape, the buildings have so much to tell now, with the passing of time and their aging. Existent research and books regarding the architectural scene are mostly in macedonian, a language I unfortunately don’t speak beyond the main courtesies and basic words. So I would leaf through books for information in the Faculty of Architecture’s library and then, by chance, find some that were published in English, and enjoy knowing a little more of the city’s urban history. When reading about a building, neighborhood or the planning history of the city, one looks at its built environment with new eyes. If you are a nostalgic and enjoy discovering the little secrets and stories that buildings and streets hold; a simple stroll in the city transforms into a complicity bond with the surroundings.

Then, I was really glad when a Macedonian friend, an architect and a scholar, so generously offered me different books regarding the architecture and urban planning of the city of Skopje, in english!

A book I particularly enjoyed reading is Biography of an Architectural work: Telecommunications center-Skopje, architect Janko Konstantinov. The book discusses a particular moment in the city’s life that exceeds the story of one of its most emblematic buildings.

In Skopje, the 1963 earthquake supposed a total rethinking of the city. When such disasters occur, a radical reflection is made. The rebuilding is more than an act of survival, but a desire for a fresh start and a basis for a visionary future development. This is where architecture and planning play a crucial role. Skopje offered to its residents a plethora of buildings during this period that will definitely shape its cityscape, public realm and even its “aesthetic” identity. This was a very exciting momentum for the city, although not free from controversy. The most influential architects and planners collaborated in its rebuilding, such as Doxiadis and Kenzo Tange, but also a whole team of “modern” Macedonian architects undertook the “shaping” of Skopje seriously.

Biography of an Architectural work is special not only because it is compiling valuable material of cultural and academic outreach, but because it is a statement and a claim: a statement that a good architecture is timeless and not a style trend, and a claim because it deserves to be protected as part of the built patrimony. As the authors say “[…] this research is aimed at determining the current position, role and importance of the prominent examples of modern architectural heritage by re-focusing upon their history”. The book is the outcome of a research and an exhibition of the building’s “biographical and archive documents” that took place in the City Museum of Skopje in 2016.

The parts of the book are clear, and for an outsider like me it directly puts the architectural work into the context. It starts with a preface written by the authors presenting the research hypothesis and stressing the intricate relation between the architect and its work. It is then followed by two essays by Vladimir Kulić and Maroje Mrduljaš. Kulić touches on the subject of experimental preservation, whereas Mrduljaš discusses the situation of modern architecture on the territory of former Yugoslavia. Both issues are of great relevance for the book’s thesis.

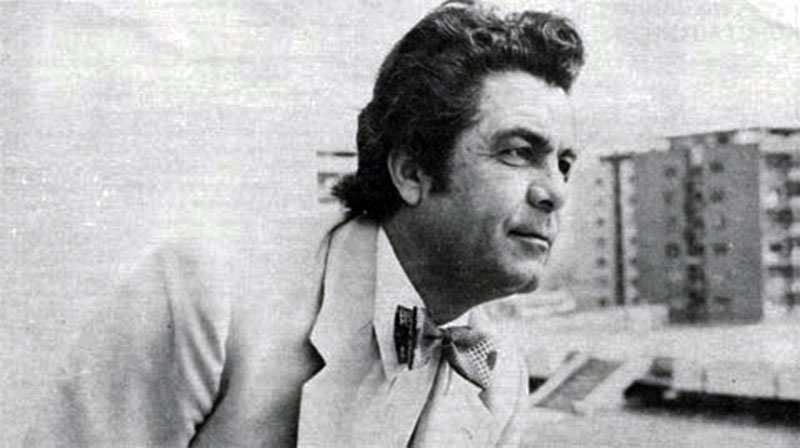

If you are strolling in Skopje along Dame Gruev avenue or Illinden boulevard and come across the telecommunications center you will know you are looking at a unique building, and will later discover, if interested, that the architect is also an exceptional personage. Master and masterpiece work in symbiosis as the book transmits us; superposing along a timeline the biography of the architect and one of the building.

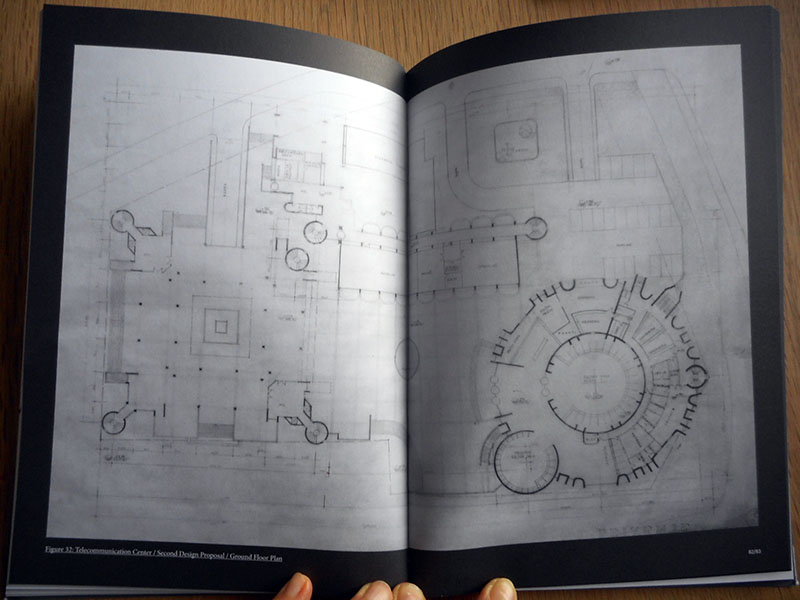

The book relies on the recently discovered personal archive of the architect. It includes graphical material published for the first time. It is very well illustrated with the original graphics and plans, international magazines reviews of the building, excerpts from the architect’s diary and photographs from the 70s, posters and graphics from retrospective exhibitions on the architect. Apart from depicting the local social-cultural context at the time the building was conceived, and its future implications on the urbanistic and architectural scene, the book refers to architectural and planning concepts of the period that affected the design process: among others illustrations of Fumihiko Maki, Arata Isozaki and Kenzo Tange. It relates the building to a coetaneous planning trend that was striving to adapt cities to the new requirements of technological and environmental progress. As the authors define the building, “The Telecommunications Center is an architectural artifact. It is one of the most important architectural and urban complexes built during the post-earthquake renewal of Skopje and an integral element of Kenzo Tange’s plan for reconstruction of the city center from 1965”. Furthermore, “it is one of the most specific local interpretations of the brutalist narrative, which in the late 1960s made a global impact on architecture and architectural development”.

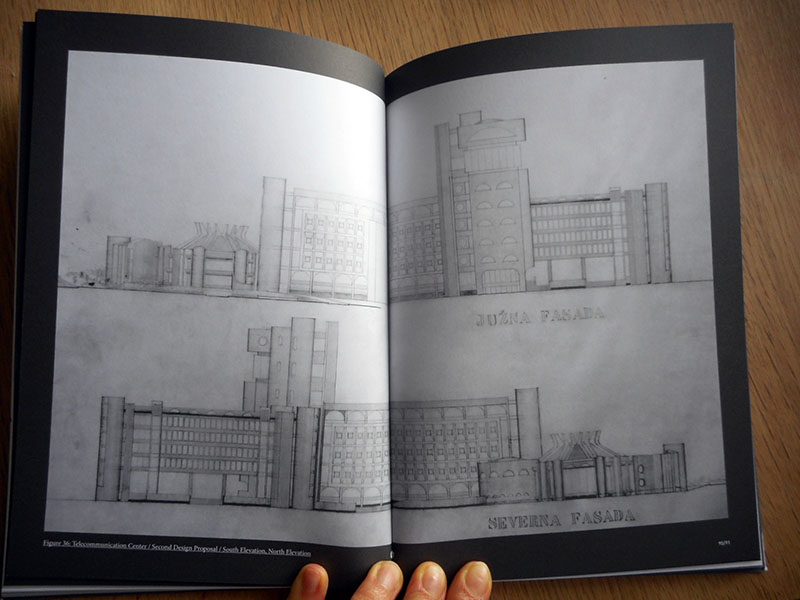

The book develops a detailed description of the architectural concepts, spatial organization of the program and building process. The realization of the Telecommunications center was not a mere act of building but a process that wasn’t free from conflicts and where the design had to face various polemics. It took over two decades to achieve the building; this evidently marked the architect’s career and explains the richness of the documents and all the discourse that this building triggered. The two different concepts and related design graphics realized for the telecommunications center between 1968-1972 are exposed in the book. Because of the technological requirements of the program, the building was divided in 3 units: the telecom postal center, the counter hall and the administrative building. This division of the main parts will mark the future development, as the units will be built consecutively. In 1972, the construction of the PTT tower and slab started and in 1978 it was in use. In 1979, the construction of the counter hall was initiated and completed in 1981. Whereas for the Administrative building, Konstantinov encountered many difficulties to achieve a final consensual design, and it is finally the architect Zoran Shtaklev who designed and built it in continuity with the concept of Konstantinov for the whole ensemble in 1989.

The Telecommunication center is not an isolated exceptional building, but one of the many that came to fill the city matrix after the 1963 earthquake along the general lines of the masterplan layered out by Kenzo Tange. As the authors observe, Konstantivov use of “meta-archaic elements” adapted the project to Tange’s vision of the city; articulated along recycled historical elements: the wall and the gate. Konstantinov studied and worked abroad, in contact with different architectural influences that will mark its aesthetic tendencies and specific treatment of its construction material: unplastered concrete. The authors refer also to the importance of the collaboration with the Institute for Studies and Design in CC Beton through all the development of the design for the 3 parts of the project. The support of the institute was crucial to developing the structures of the building but also the modular elements shaping the facades. The possibility of prefabrication and “cut-to-size” manufacture allowed the appearance of such modular specimens specific to the building. Apparently, this technique was widely spread in Yugoslavia as Maroje Mrduljaš points out. With Konstantinov concrete gained a great plasticity, shaping along brutalist and expressionist lines to finally acquiring a style that will distinguish the architect. Being a member of the Group Denes (an artistic endeavor aiming at the creation of contemporary art and composed of painters, architects and sculptors), Konstantinov was one of the first to “encourage the integration of architecture and arts” and escaped any clear architectural style classification.

The last part of the book, entitled “Transition” positions the building in the contemporary context. It is true that the services offered by the center remain mostly obsolete in the current digital age, and this affects the programmatic distribution of the building and questions its future use. But most importantly, the authors denounce the unprotected situation of the building in the face of different dilapidations. In 2013, a fire in the counter hall of the center damaged the structure and destroyed the mural frescoes by painter Borko Lazeski. For Skopje 2014, the Administrative building was buried under heavy neoclassical accoutrement, in intent of nation building through historical imagery. And then the unity of the public free space around the building, essential to its concept, was shattered by two awkward buildings that disfigured its initial perception.

The telecommunication center didn’t escape the faith of most of the ex-Yugoslav architectural heritage: falling into disgrace. This socialist brutalist building legacy contests politics of conservation, the collective memory selective apparatus and the cultural identity attributed to the city. As Vladimir Kulić say “[…] of all of eastern Europe, it is in the former Yugoslavia that the incorporation of the socialist period into the new national(ist) narratives faces such a challenge.” Is it because this common socialist building simplified the nuances between the different cultures under a homogenized new geographical identity, and now there is a need to recuperate evasive identities and national imaginaries, after the disintegration of this unity? The case of Skopje is particular, because it is not just negligence to protect its modernist patrimony but almost an undertaking of actions to promote its disappearance from the collective urban memory and cityscape at once. That is why these buildings of the modern heritage of Skopje, are relevant beyond their mere architectural achievements becoming social-cultural artifacts and political stakes.

The book is a milestone in the process towards assessing the architectural heritage of Skopje and the valorization of the modernist architecture as a relevant characteristic of the urban landscape of the city. In the actual situation, this book is almost a “political act” that goes beyond “architectural historiography” as Nebojša Vilić, a prominent art critique and curator in Skopje, comments in the final note of the book.

The book as any good book, sends you to explore new horizons: “Modernism in-between: Mediatory Architectures of Socialist Yugoslavia” and “Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948–1980” illustrated with amazing photographs of Valentin Jeck; a tribute to this exceptional architecture.