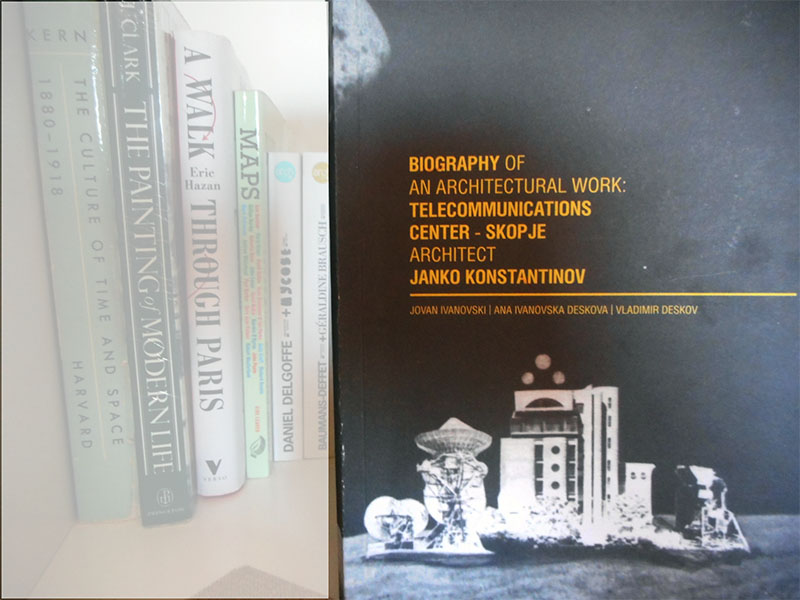

Dear readers, this is an unusual post. Probably the last one I will write from Skopje, as I am getting ready to move to Sarajevo by the end of the month of July.

I have been living in Skopje for over 2 years now and my frustration keeps on regarding my knowledge of the built environment. So many things to tell, and so little I know; it brings a sigh each time one of these buildings that stand proudly in the cityscape catches my eye. Some are old and decrepit like the

The trains were lying on the railways waiting for the dawn, the platforms where still empty, soon to be filled with the passengers and the agitation of early morning. But this wasn’t to be an ordinary day for the station.

I usually go from my house in Crniče to the city’s center walking. Sometimes I take one of the shortcuts that weave their way down the hill, cutting through the dense tree foliage in summer.

Winter is already here. The trees have lost their leaves, slowly, in constant but irreversible change of browning shades, until they totally fell and vanished.