A table with a view is a glad to be part of this very exciting venue in Sarajevo. The exhibit Les Sentiers Métropolitains produced by the Pavillon de l’Arsenal and curated by Paul-Hervé Lavessière and Baptiste Lanaspeze of the Metropolitan Trails Agency.

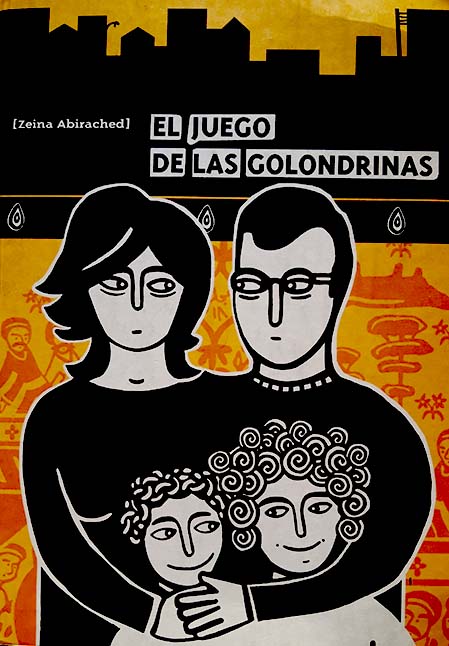

I was so happy to receive, in Sarajevo, my compatriot Zeina AbiRached book: Le jeu des Hirondelles: Mourir, partir, revenir. I received it in the Spanish version under the title “EL juego de las golondrinas”.