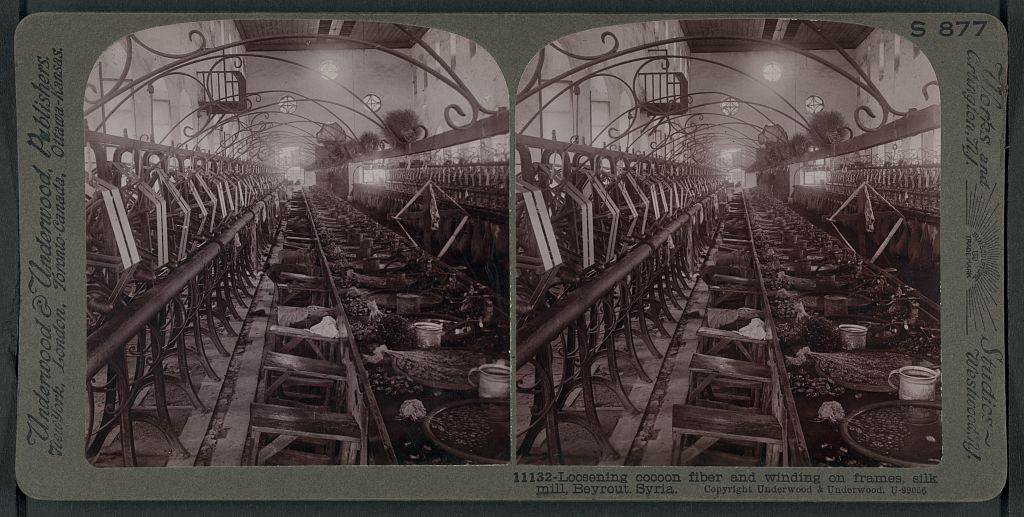

The ongoing 16E Bienniale d’Art Contemporain of Lyon stages the life of Louise Brunet as the major inspiration for the Biennale’s theme: Manifesto of Fragility (https://www.labiennaledelyon.com/manifesto-of-fragility-menu). The aim is to shed light on the micro-stories often pulled aside in the making of the historical meta-narration; and Louise, a silk spinner from Lyon that ended up in Mount Lebanon, becomes the symbol of all these stories untold through time. Variegated art pieces and installations try to grasp this sense of fragility in fleeting narratives enclosed in objects, archive, relics, sculptures, reframing a history of the intimate in an anachronic fashion escaping from Historical time.

Beirut is very present in the biennial through many artistic representations, and it is no wonder, because it has been the product, the spatial construction of this historical meta-discourse. A city on the periphery, its birth as a capital is a micro-story in relation to the History unfolding in the mid XIXth century and the construction of a world system. The superposition of Lyon and Beirut, inevitably brought to my mind the work I did on urban Beirut between 1830-1920 in 2014* that studied Beirut as an extended territory of production in relation to the metropolis, Lyon, and all the consequences it had on her urban growth within a dying Ottoman empire, culminating in the creation of Lebanon.

The city came to being as the capital of Grand Lebanon on the 1st of September 1920 in a declaration by French general Gouraud. Before, its situation was best described in this conversation at the Quai d’Orsay in October 1919:

Philippe Berthelot: Mais Beyrouth fait partie du Liban.

Emir Faisal: Beyrouth n’est pas compris dans les frontières du Liban actuel.1

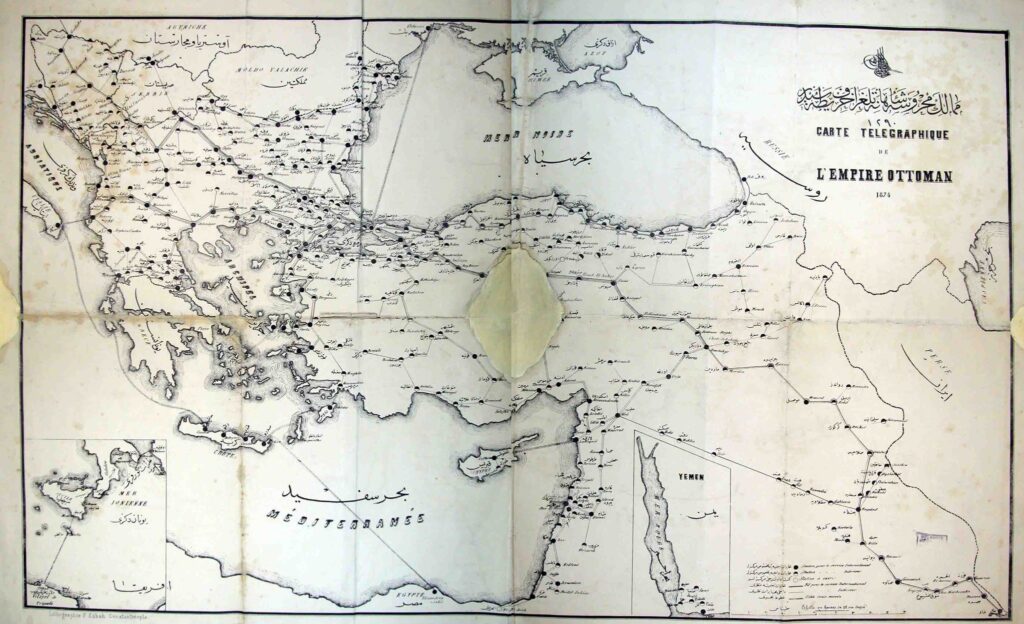

Too many interests were at stake to keep Beirut as a free port. Mount Lebanon was the main provider of silk to the factories in Lyon after the pébrine disease in the mid XIXth century disseminated the silkworms in a plague that extended in France and Italy. The Ottoman’s had already spread the telegraph network for financial transactions and investments in local infrastructure as soon as 1874, Comte De Perthuis had achieved the founding of the Beirut port company in Paris in 1886, and when Gouraud arrived to Lebanon, he had to create a territoriality that would suit needs of the metropolis (France) and its local partners.

The construction of Lebanon has been commented as follows by George Fayyad in a letter to Alfred Sursock “it is a monster as it head [Beirut] is bigger than its body” 2. I can´t help but think of the figure of the minotaur, trapped in the labyrinth, but this time a silk thread won´t do, the sacrifices to keep it alive, since its birth until now, didn´t stop.

The creation of Lebanon, consisting of territorial annexations, such as Beirut, Sidon, Tripoli and the Bekaa valley to Mount Lebanon is a micro-story within the big lines of history shaping the world at the beginning of the XXth century; but that is vital to understand the spatialities we are living in, be it at the usines Fagor of Lyon or in a city like Beirut. Micro narratives occur at different scales.