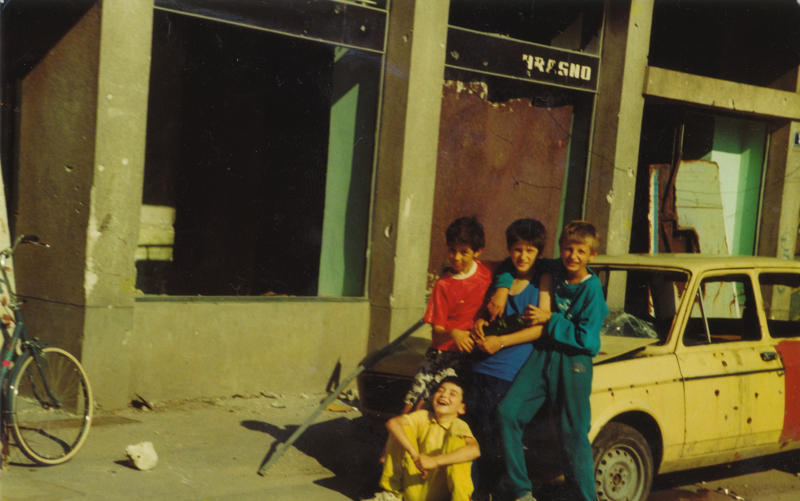

1992-1996, the city of Sarajevo is under siege and the children cannot attend school, play or move as freely as they would like. But scattered initiatives started to provide children with a basic need: schooling. A person, often a professor, will gather the children hiding in the basement of the building and some others from the vicinity and will organize a class. These initiatives will quickly build up into a local school system put in place by the Pedagogical Institute of the city to pursue schooling during the war and under the extreme conditions of siege that the city of Sarajevo was painfully undergoing.

For the past two years, while living in Sarajevo, I came across a book titled The heroes of Treća Gimnazija by the american pedagogue David M. Berman. In his book, Berman narrates how schooling was carried on in the city of Sarajevo during the war and siege that took place between 1992 and 1996. Starting as scattered initiatives in basements,

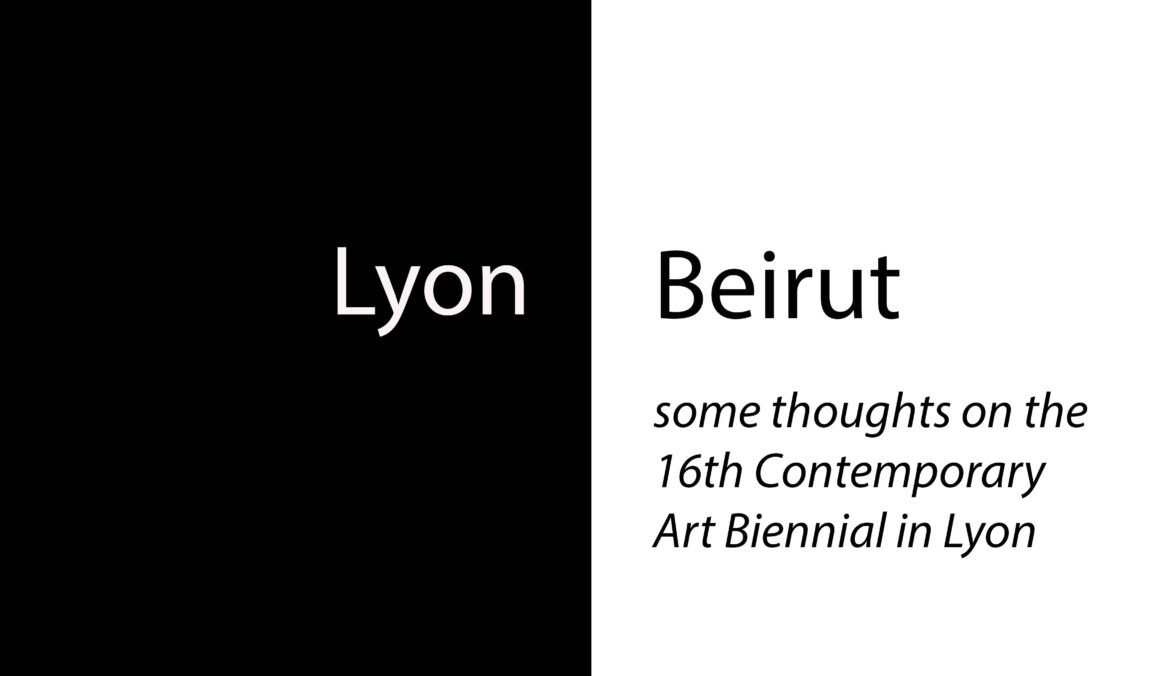

The ongoing 16E Bienniale d’Art Contemporain of Lyon stages the life of Louise Brunet as the major inspiration for the Biennale’s theme: Manifesto of Fragility. The aim is to shed light on the micro- stories often pulled aside in the making of the historical meta-narration;

A table with a view is a glad to be part of this very exciting venue in Sarajevo. The exhibit Les Sentiers Métropolitains produced by the Pavillon de l’Arsenal and curated by Paul-Hervé Lavessière and Baptiste Lanaspeze of the Metropolitan Trails Agency.

On the 13th of January 2022, I received an invitation from my friend, the artist-pedagogue Jean-François Pirson, to intervene in one of his projects. The invitation’s postcard was accompanied by two maps of the Dunkirk region, in risograph printing.

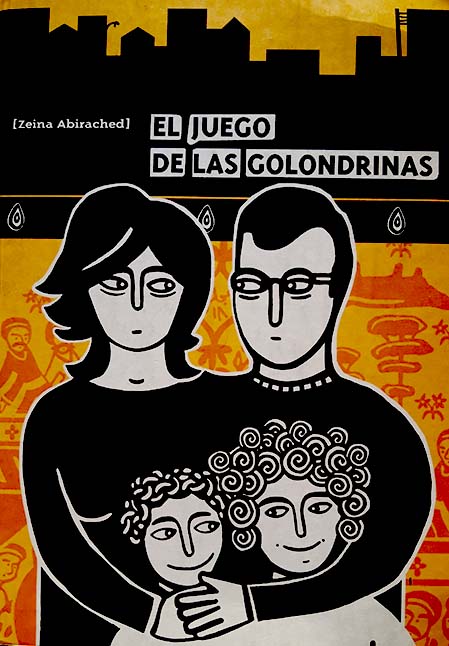

I was so happy to receive, in Sarajevo, my compatriot Zeina AbiRached book: Le jeu des Hirondelles: Mourir, partir, revenir. I received it in the Spanish version under the title “EL juego de las golondrinas”.

Last Monday I had a different walk in Sarajevo; this time it can be defined as “urban” in comparison with the previous walks on the surrounding hills, and “in company” instead of solitary. This walk was led by Goga and Elmir, a couple in love with the “other” Sarajevo, the one beyond the historic centre: Tito’s Sarajevo.

This is the second part of my first spring walk in Sarajevo, following a path leading to Sedrenik and Barice, and if you continue up further to Čavaljak. These are locations that are predilection outings for city dwellers in the weekend. This time I was back up

This has been a long winter. For man and nature. Here in Sarajevo the continuous snowing and the pandemic left the city in a hibernating state.

That is why, with the advent of spring, the first glimpse at a blue sky is encouraging enough to take a walk. The mountains surrounding Sarajevo shed their brownish rags and changed into a shiny verdant garment.

When I knew I will be leaving Skopje to live in Sarajevo for the next three years, I was happy and sad, and a little superstitious. Superstitious, because I first moved from my hometown Beirut to Barcelona, then from Madrid to Malabo and now from Skopje to Sarajevo, what will the next two cities be following this alphabetical rhythmic, what will be the next letter?